Posts: 12,025

Threads: 1,809

Joined: Apr 2008

Reputation:

227

by Bill McBride on 4/11/2013 11:58:00 AM

From a research note by Goldman Sachs chief economist Jan Hatzius: The Rapidly Shrinking Federal Deficit

The federal budget deficit is shrinking rapidly. ...[I]n the 12 months through March 2013, the deficit totaled $911 billion, or 5.7% of GDP. In the first three months of calendar 2013--that is, since the increase in payroll and income tax rates took effect on January 1--we estimate that the deficit has averaged just 4.5% of GDP on a seasonally adjusted basis. This is less than half the peak annual deficit of 10.1% of GDP in fiscal 2009.

There are three main reasons for the sharp reduction in the deficit:

1. Lower spending. On a 12-month average basis, federal outlays have fallen by a total of 4% in the past two years, the first decline in nominal dollar terms over a comparable period since the demobilization from the Korean War in the mid-1950s.

2. Higher tax rates. The increase in payroll tax rates in January 2013 has boosted federal receipts by around $120 billion (annualized), or about 0.8% of GDP.

3. Economic improvement. Although real GDP has only grown at a sluggish 2%-2.5% pace since the end of the 2007-2009 recession, this has been enough to generate a sizable improvement in tax receipts, over and above the more recent impact of higher tax rates. Even prior to the tax hike that took effect in early 2013, total federal receipts had grown by 7% (annualized) from the 2009 bottom, nearly twice the growth rate of nominal GDP.

We expect the deficit to continue to decline and are forecasting a deficit of 3% of GDP or less in fiscal 2015. Some of this is policy-related. ... But the more important reason, in our view, is that there is still a great deal of room for the economic recovery to reduce the deficit for cyclical reasons. ...

In our view, the most important implication from the reduction in the budget deficit for the near-term economic outlook is reduced pressure for further fiscal retrenchment. Partly for this reason, we expect the drag from fiscal policy on real GDP growth to decline sharply from around 2% of GDP in 2013 to around 0.5% in coming years. This is a key reason for our expectation that real GDP growth will accelerate from around 2% (annualized) in Q2/Q3 2013 to 3%-3.5% in 2014-2016.

It shocks people when I tell them the deficit as a percent of GDP is already close to being cut in half (this doesn't seem to ever make headlines). As Hatzius notes, the deficit is currently running under half the peak of the fiscal 2009 budget and will probably decline further over the next few years with no additional policy changes.

Posts: 12,025

Threads: 1,809

Joined: Apr 2008

Reputation:

227

Moreover, fiscal austerity continues to bite:

Posts: 12,025

Threads: 1,809

Joined: Apr 2008

Reputation:

227

by Joseph E. Gagnon | May 24th, 2013 | 11:23 am

Last week, Tyler Cowen of the blog Marginal Revolution asked “Have we seen self-defeating austerity in the United States?” Cowen declines to take a clear stand on the question, but his main point is that the well-known fiscal cuts of 2012 and 2013 have, in fact, reduced the US budget deficit. Ergo, goes the implication, austerity was not self-defeating.

The problem is that the case for self-defeating austerity—described in a blog post by Paul Krugman and a paper [pdf] by Brad DeLong and Lawrence Summers to which Cowen provides links—focuses on the long-run fiscal impact. Both accounts concede that austerity reduces the deficit in the short run. Their argument is that in the current environment of near-zero interest rates, fiscal deficits are unusually cheap to finance and monetary policy is not going to move to offset much (if any) of the effects of fiscal policy on the economy. Under these conditions, it is indeed possible that austerity today may reduce future tax revenues by so much that the national debt ends up larger than it would have been without austerity.

The relevant question is how much stronger would US economic growth be this year and in future years if the Congress and the administration had delayed tax hikes and spending cuts another year or more. Jackie Calmes and Jonathan Weisman of the New York Times report that private-sector economists estimate that growth would be almost 2 percentage points higher. A growth rate of around 4 percent is consistent with historical norms for recovery from a deep recession; the current rate of around 2 percent is abnormally low given the large excess capacity in the economy.

At least part of this extra growth would have taken the form of business investment that would have supported durable gains in future economic activity. Even more important, Calmes and Weisman report that unemployment would be about 1 percentage point lower. Many economists believe that allowing people to remain out of work for long periods of time permanently reduces their skills and attachment to the labor force and thus reduces economic output for decades.

The case that austerity is self-defeating hinges on the long-lasting reduction in tax revenues associated with the lower economic growth caused by austerity. In the current unusual circumstances, it is possible that this year’s austerity will reduce future economic activity by so much that the decline in future tax revenues will ultimately outweigh any near-term reduction in our national debt, leaving national debt even larger relative to the US economy than if the austerity were delayed to a period of lower unemployment and higher interest rates.

We cannot be sure whether the conditions for austerity to be self-defeating are fully met at present, but it is clear that this year’s austerity, and the associated improvement in the US fiscal position, have been achieved only at an enormous price in terms of long-term unemployment and reduced economic growth. And even if this year’s austerity does not make our long-run debt burden heavier, it surely does not reduce it by enough to justify the hardship it has imposed on millions of Americans.

Posts: 12,025

Threads: 1,809

Joined: Apr 2008

Reputation:

227

The piece above by Magnon is about the shortest and most clear about the arguments against austerity under present conditions. These present conditions are:

-

The aftermath of a financial crisis, where the private sector is recovering their damaged balance sheets by borrowing and spending less.

-

As a result, the economy produces way below capacity, resulting in high unemployment and plants that are not fully used so there is little incentive for business to expand investment.

-

The combination of low credit demand (households repairing balance sheets, firms not expanding production capacity) and monetary policy produce very low interest rates.

Under these circumstances (called a balance sheet recession):

-

Monetary policy is relatively powerless as even record low interest rates do not revive borrowing and spending by all that much

-

Fiscal policy is unusually effective due to the record low interest rates and the lack of 'crowding out' (due to high savings and low credit demand increased public borrowing isn't likely to increase interest rates and 'crowd out' private sector credit demand).

Austerity (reducing public spending and/or increasing tax rates) can easily compound the tepid private spending and have a large adverse effect on economic growth because It cannot be offset by more expansionary monetary policy as interest rates are already rock bottom.

So austerity is likely to have a larger negative effect on economic growth than usual, but there is another effect. The longer the economy produced below full capacity, the more future economic capacity will be damaged and the lower future economic growth will be:

-

Low demand and capacity utilization slows business investment, production capacity increases more slowly than would otherwise be the case and the existing capital stock deteriorates as it isn't renewed as fast, slowing productivity growth

-

The longer people stay unemployed, the less their chance of future employment, that is, labor also deteriorates slowly.

This hysteresis effect, as it's called, hampers production when demand finally recovers, as it slowly deteriorates existing production factors. Austerity, under present conditions, could therefore have long-run negative growth consequences, and therefore also negative consequences for future tax receipts, in which case it can become self-defeating, that is, not leading to improved public finances.

Posts: 2,904

Threads: 58

Joined: Mar 2012

Reputation:

259

Back in 2009 when the stimulus program was announce there was over 100 billion announced for civil projects that were "shovel ready". It took years to spend most of that money. There were 't the engineers, contractors and skilled trades to get that volume of work done, despite the glaring need for infrastructure repairs in this country. Losing skills daily.

Posts: 12,025

Threads: 1,809

Joined: Apr 2008

Reputation:

227

Yes, and despite the recovery in the economy, in house prices and in private wealth, manufacturing is still running way below capacity:

http://www.businessinsider.com/america-h...ity-2013-6

Posts: 12,025

Threads: 1,809

Joined: Apr 2008

Reputation:

227

How fast things can change..

Posts: 12,025

Threads: 1,809

Joined: Apr 2008

Reputation:

227

By Jeanne Sahadi @CNNMoney October 30, 2013: 5:31 PM ET

NEW YORK (CNNMoney)

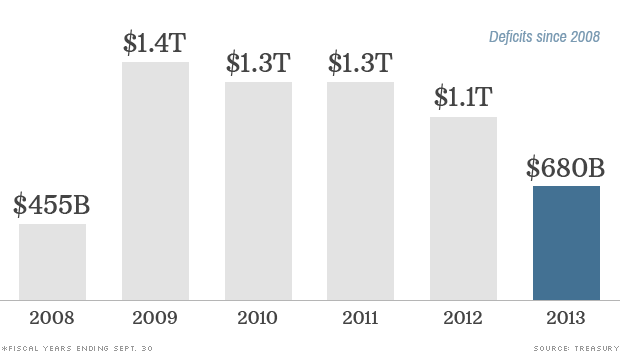

The federal government's latest annual deficit is the smallest it's been since 2008, according to Treasury Department data released Wednesday.

At $680 billion, the fiscal 2013 deficit is 51% less than it was in 2009, when it hit a record high nominally of $1.4 trillion.

As a percent of the economy, it's also considerably smaller than it's been in the past five years, coming in at 4.1% of gross domestic product. By contrast, the annual deficit in 2009 topped 10% of GDP. And last year it was 6.8%.

Overall, Treasury said higher receipts accounted for 79% of the decline in the deficit from last year.

Related: Washington's budget fiasco

Several factors have contributed to the strong improvement in the nation's near-term fiscal picture. They include an improving economy and a mix of fiscal restraint -- primarily, the expiration of stimulus measures, the imposition of across-the-board budget cuts known as the sequester, and tax increases on high-income households during the 2013 fiscal year, which ended September 30.

Another boon was the fact that Fannie Mae (FNMA, Fortune 500) and Freddie Mac (FMCC, Fortune 500) paid back a large part of the $187 billion federal bailout the mortgage giants received, starting in 2008, to help them weather the housing crisis.

In addition, total interest payments -- $415.6 billion -- were moderate relative to the amount of outstanding debt and GDP, but were nearly 16% higher than in 2012.

Overall, spending in 2013 totaled 20.8% of GDP, down from 22% the year before, thanks in part to declines in defense spending and unemployment benefits, as well as the sequester. Among the areas where annual spending rose were Social Security and Medicare.

Money going into federal coffers reached 16.7% of GDP, up from 15.2% in 2012. Tax receipts from individuals and estate and gift taxes saw the biggest percentage jumps, and most major categories of receipts were higher too.

Treasury's latest data for 2013 were delayed by a few weeks due to the 16-day partial government shutdown that began on October 1.

The report also came as a new bipartisan group of lawmakers have begun to work toward a budget deal to at least ensure funding continues for the rest of fiscal year 2014 and to resolve whether or not to replace the sequester.

Either way, fiscal restraint is likely to continue for the next couple of years. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that the annual deficit will fall to a low of 2.1% of GDP in 2015, before starting to rise again thereafter.

Independent budget experts' concern, however, is not about the country's deficits over the next 10 years. Their concern is about the subsequent decades when spending on major entitlement programs, as well as interest on the debt, will consume much larger portions of the budget while revenue is not expected to increase enough to keep pace.

|