Posts: 12,025

Threads: 1,809

Joined: Apr 2008

Reputation:

227

RICHARD KOO: Japanese Stocks Crashed Because The Japanese Knew Something That Foreign Investors Didn't

Matthew Boesler | Jun. 4, 2013, 11:55 AM | 796 | 3

Fung Global Institute

In his latest piece, Nomura economist Richard Koo examines the recent crash in the Japanese stock market, which has tumbled 15% since just May 22.

"The prevailing view is that we are finally seeing a reaction to this excessively rapid move, and if so this is a healthy correction," he begins. "The reality, however, may be somewhat more complicated."

Koo argues that the primary driver of the big upward move in the Japanese Nikkei 225 so far has been hedge funds outside of Japan who were previously betting against the euro.

Then, last September, when the ECB introduced a new monetary stimulus program that undermined the fear in the market that the euro could collapse, those international hedge funds had to find something else to bet against.

Koo writes (emphasis added):

Late last year, the Abe government announced that aggressive monetary accommodation would be one of the pillars of its three-pronged economic policy. Overseas investors responded by closing out their positions in the euro and redeploying those funds in Japan, where they drove the yen lower and pushed stocks higher.

I suspect that only a handful of the overseas investors who led this shift from the euro into the yen understood there was no reason why quantitative easing should work when private demand for funds was negligible. Had they understood this, they would not have behaved in the way they did.

Japanese investors, Koo asserts, did understand this. That's why they didn't join in when international hedge funds started buying up Japanese stocks in size (emphasis added):

Whereas overseas investors responded to Abenomics by selling the yen and buying Japanese stocks, Japanese institutional investors initially refused to join in, choosing instead to stay in the bond market.

Because of that decision, long-term interest rates did not rise. That reassured investors inside and outside Japan who were selling the yen and buying Japanese equities, giving added impetus to the trend.

However, Japanese investors' initial aversion to the long Nikkei trade couldn't last forever.

"Even though the moves in the equity and forex markets were led by overseas investors with little knowledge of Japan," says Koo, "the resulting improvement in sentiment and the extensive media coverage of inflation prospects forced domestic institutional investors to begin selling their bonds as a hedge."

That selling caused yields and volatility to rise in the Japanese government bond market, which spooked investors and arguably sparked the big unwind in the Nikkei trade.

But why should rising bond yields be such a bad thing for the "Abenomics" story of experimental economic stimulus in Japan that international investors have placed their faith in by running up Japanese stocks? After all, higher yields reflect rising inflation, which is one of the main goals of Abenomics.

The problem, according to Koo, is that a rise in inflation before the Japanese economy starts to recover is bad news:

The Bank of Japan began buying longer-term JGBs on 4 April with the goal of pushing yields down across the curve. The outcome of those purchases, however, has been exactly the opposite of what Governor Haruhiko Kuroda intended, with long-term bond yields moving higher in response.

Domestic mortgage rates have increased for two consecutive months as a result. This is clearly an unfavorable rise in rates driven by concerns of inflation, as opposed to a favorable rise prompted by a recovery in the real economy and progress in achieving full employment.

The more the market senses the BOJ’s determination to generate inflation at any cost, the more interest rates—and particularly longer-term rates—will rise, adversely impacting not only Japan’s economy but also the financial positions of banks and the government...

Since there is no increase in bank earnings from additional lending activity and no increase in tax revenues from a recovering economy, the financial positions of banks and the government deteriorate in direct proportion to the rise in long-term interest rates.

In other words, rising rates aren't bad if they reflect a strengthening economy, because the losses banks will sustain in their bond portfolios will be offset by increased revenues owing to a stronger economy in general.

Again, though, Koo does not think that is the scenario unfolding in Japan right now:

Only 22% of people surveyed by the Nikkei felt Japan’s economy is actually recovering (27 May 2013), suggesting relatively few have benefited from Abenomics’ honeymoon thus far.

Moreover, an increase in long-term rates at a time when 78% of the population is not personally experiencing a recovery is most likely a “bad” rise in rates, and the authorities need to address it very carefully, keeping a close eye on private demand for funds.

All of this means that the big upward thrust in Japanese equities that began late last year has likely come to an end, at least for now.

"The recent upheaval in the JGB market signals an end to the virtuous cycle that pushed stock prices steadily higher," says Koo. "This means further gains in equities will require stronger corporate earnings and a recovery in the economy."

MORE — DEUTSCHE BANK: We Don't See A Bottom In Japanese Stocks >

Read more: http://www.businessinsider.com/richard-koo-explains-the-japanese-stock-market-crash-2013-6#ixzz2VGixiQig

Posts: 12,025

Threads: 1,809

Joined: Apr 2008

Reputation:

227

by Joseph E. Gagnon | June 14th, 2013 | 04:11 pm

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe captured the attention of economists, pundits, and global markets with his bold plans to boost growth and inflation in Japan. Stock prices soared, real bond yields plummeted, and the yen dropped sharply. These trends boded well for Abe’s success. More recently, markets seem disappointed with the details (or lack thereof) on Abe’s structural reforms and the unwillingness of the Bank of Japan (BOJ) to implement its quantitative easing (QE) plans flexibly. In this post I focus on what the BOJ should do to achieve its inflation goal and how that will help reduce the long-run burden of Japan’s large national debt.

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), net government debt in Japan is already a worrisome 145 percent of GDP and still growing (compared to 90 percent and stable in the United States). It is well known that countries often grow or inflate their way out of large debt burdens. The United States did some of both after World War II. The dollar value of debt grew slower than the dollar value of the US economy for decades, causing debt to shrink by more than half when measured as a percent of GDP. Japan needs to apply a similar economic magic.

I leave it to others to discuss the structural reforms Japan needs to raise its long-run growth rate. I focus on raising inflation to the new target of 2 percent. Many observers argue that higher inflation can have only a small effect on the fiscal position of a country with sophisticated and open financial markets like Japan. Any attempt to raise inflation, they say, will raise the interest rate Japan must pay on new debt issues by an equal amount. The only cost savings will be on the stock of debt that was issued before the rise of inflation, and that is a relatively modest, one-off gain.

But the behavior of bond markets belies this argument. Figure 1 shows that between Abe’s election in mid-December (marked by the vertical line) and the middle of last month, the real yield on inflation-indexed bonds fell about 1 percentage point1 The nominal yield rose less than 0.2 percentage point, implying that expectations of long-run inflation in the bond markets rose more than 1 percentage point. Thus, bond markets expected that Japan would indeed be able to inflate away a significant portion of its debt. Each percentage point decline in the real interest rate on Japan’s debt is equivalent to a cut in the fiscal deficit of 1.5 percent of GDP.

Figure 1 Bond Yields in Japan, September 3, 2012 to June 13, 2013

In recent days, some of these moves have been reversed, suggesting that markets are beginning to doubt the BOJ’s resolve. Currently, long-term inflation expectations are around 1 percent, well below the 2 percent target.2 However, despite the recent market reversals, inflation expectations remain significantly higher than before Abe’s election, as are equity prices, while the yen is lower. This suggests that QE is having an important effect in the intended direction. What more needs to be done?

The BOJ needs to state clearly that it is willing to adjust the size, speed, and composition of QE as needed to achieve its target. Although the BOJ’s plan to buy long-term bonds worth around 25 percent of GDP over the next two years is certainly bold, we simply do not know how bold is bold enough. Here are three steps the BOJ could take to increase the effectiveness of its policy: (1) accelerate already planned bond purchases in a flexible manner with an eye toward damping volatility in nominal bond yields; (2) dramatically raise the share of QE devoted toward purchases of equity, which may have larger economic benefits than purchases of bonds; and (3) increase the total volume of QE until inflation expectations in bond markets reach the 2 percent goal.

As the saying goes: in for a penny, in for a pound. The BOJ has staked its credibility on achieving 2 percent inflation within two years. Now is not the time to get cold feet.

Notes

1. Yields are based on composites of government bonds with maturities up to 10 years.

2. Expectations are derived from the difference between nominal and real bond yields. This difference is adjusted downward by about one-half of a percentage point to remove the effects of the planned consumption tax increase on future inflation. The consumption tax was legislated last August, well before Abe’s election.

Permalink | Send comments

Tags: debt, fiscal policy, inflation, Japan

Posts: 12,025

Threads: 1,809

Joined: Apr 2008

Reputation:

227

This is is a guest post from Philip Pilkington, a writer and research assistant at Kingston University.

Well, it seems that everyone is talking about Japan’s Shinzo Abe’s so-called “Fourth Arrow” in his economic recovery program. That is, a plan to raise the consumption tax to eight per cent next year followed by a hike to ten per cent in October 2015. Can we tell anything about the likely consequences of such a move from Japan’s rather colourful macroeconomic history of the past twenty years? Yes, we can.

Japan has had quite a lot of experience with both stimulus and tax hikes, which makes it far easier to forecast what might happen if the Fourth Arrow is indeed shot from Abe’s bow in the near future than it might be in a different country.

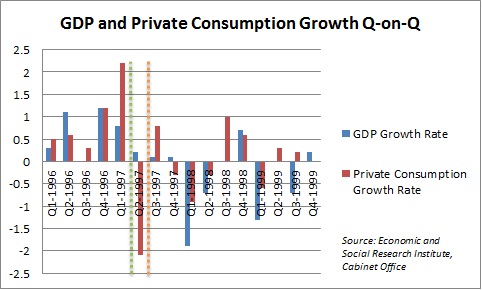

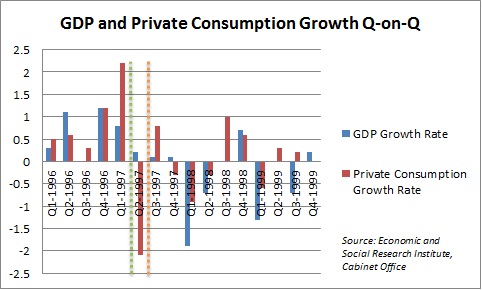

In 1997 the Japanese government engaged in some fiscal retrenchment and raised the consumption tax from three to five per cent. Soon after this policy was enacted there was a recession and a sharp increase in Japan’s government debt-to-GDP ratio – the very variable the tax increases were presumably supposed to target.

Some have sought to pin all of the blame for the recession on the East Asian financial crisis. The figures, however, tell a more complex story. In the below graph the green dotted line shows when the consumption tax was levied (April 1997), while the orange dotted line shows when the Asian financial crisis began (July 1997). As can be seen the consumption tax was followed by an immediate drop in consumption and decline in GDP growth prior to the financial crisis occurring.

It is clear that upon being levied the consumption tax had an immediate and dramatic effect on consumption. Indeed, from 1994 until the first quarter of this year the fall in consumption in the second quarter of 1997 is the largest on record.

While it is probably true that a significant part of the 1998 recession can be blamed on the Asian financial crisis, the effects of the consumption tax are nevertheless quite clear and quite dramatic when we examine the data closely. And the fall in GDP before the Asian crisis fully kicked in suggests just looking at the reasonably predictable bounce and fall in consumption around the tax increase might not be enough.

UPDATE 1810: And if we take the average quarterly growth rates in consumption on both sides of the imposition of tax — while not counting the two periods immediately prior to and after the tax, nor counting the period of the 2008 financial crisis and the effects of the stimulus that followed — we find that the average growth rate of consumption prior to the tax was 0.53 per cent and the average growth rate after the tax was only 0.08 per cent. Clearly then, the imposition of the consumption tax had substantial long term effects.

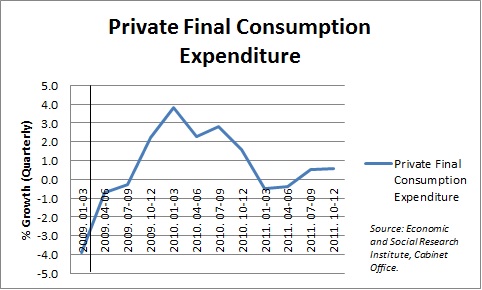

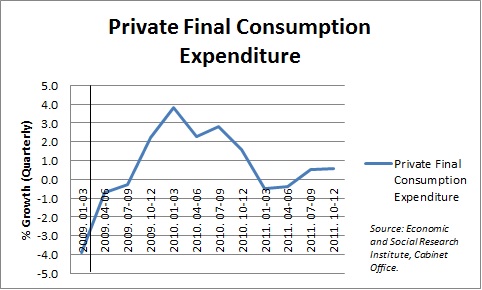

But there is also a broader picture that needs to be taken into account here. Low consumption seems to be an ever present problem for the Japanese economy – one might even say that it is the most important problem that the Japanese face. A good way to get an idea of this – and one which will help us forecast the potential effects of Abe’s Fourth Arrow – is to look at the effects of the 2009 stimulus.

In April of 2009, in response to the massive downturn in the world economy, the Japanese government announced a substantial stimulus of 3 per cent of GDP. The effects on consumption, as can be seen in the graph below, were as dramatic as they were short-lived.

The vertical black line indicates when the stimulus was announced. As we can see, private sector consumption briefly jumped from its post-2008 lows but then quickly subsided once more. This reflects a major structural problem with the Japanese economy: consumers just don’t seem that inclined to consume.

This is frequently noted in Japan and various reasons are given, from an aging population to a culture of underconsumption that formed in Japan after the excesses of the 1980s.

Whatever the causes, however, the lesson should be clear: consumer spending is the lifeblood of any advanced economy and any program geared toward economic recovery in Japan that incorporates measures that will dampen consumer spending is likely to fail. The question now is whether political pressure will lead Abe to string the bow.

Posts: 12,025

Threads: 1,809

Joined: Apr 2008

Reputation:

227

Japan refuses to go quietly into genteel decline. The revolutionary policies of premier Shinzo Abe have done exactly what they were intended to do – a triumph of political will over the defeatist inertia of Japan's establishment.

"Abenomics is working," says Klaus Baader, from Societe Generale. The economy has roared back to life with growth of 4pc over the past two quarters – the best in the G7 bloc this year. The Bank of Japan's business index is the highest since 2007. Equities have jumped 70pc since November, an electric wealth shock.

"Escaping 15 years of deflation is no easy matter," said Mr Abe this week, after winning control over both houses of parliament, yet it may at last be happening.

Prices have been rising for three months, and for six months in Tokyo. Department store sales rose 7.2pc in June from a year earlier, the strongest in 20 years.

Japanese retail sales have grown recently, albeit in a fairly volatile fashion, and reached a new peak in May.

"Above all, Abenomics has shifted the yen," said Mr Baader. The 22pc devaluation since October has held, rather than snapping back as usual. The psychology of yen appreciation is breaking. Exports have jumped 7.4pc from a year ago.

The nasty side-effect is a deflationary trade shock for China, now paying the price for pegging its currency to the US dollar. Veterans will remember the Asian crisis in 1997-98 when Fed tightening slowly choked China's economy.

Yet for Japan the weak yen is the Holy Grail. We forget that it rose 45pc on a trade-weighted basis from 2007 to late 2012, and by 70pc against the euro and 90pc against Korea's won. The strong yen -"Endaka" – had itself become the driving force of deflation.

Abenomics has not caused a collapse of confidence in Japanese debt after all. The bond vigilantes are, for now, resigned, as the Bank of Japan soaks up 70pc of state bond issuance each month, printing almost as much money as the Fed in an economy one third the size.

The alarming spike in yields after the new team of Haruhiko Kuroda took over in the Spring has subsided. Ten-year rates are back to 0.77pc, where they were last year, and much lower in real terms.

The BoJ's adventure could still go horribly wrong but matters were absolutely certain to go horribly wrong under the hand-wringing caution of the previous team. By doing almost nothing they switched the burden of stimulus on to fiscal policy, one spending blitz after another, each fizzling out before reaching "escape velocity", all ending in an explosion of public debt.

Nominal GDP has shrunk by 10pc since 1998, a monetary crime. Yet debt has tripled.

The denominator effect is lethal. The IMF says Japan's gross debt was 216pc of GDP in 2010, 233pc in 2011, 238pc in 2012 and will reach 245pc this year. This is already a debt-compound spiral.

Mr Abe had to confront this head-on before the cataclysm hit. He has done so by turning to the ideas of Takahashi Korekiyo, the statesman of the early 1930s, later assassinated by military officers.

Takahashi tore up the rule book and combined monetary and fiscal stimulus, each reinforcing the other, until Japan was booming again, and the debt trajectory came back under control. The BoJ became a branch of the treasury, ordered to finance spending.

"What he accomplished was what can be called the most successful application of Keynesian policies," said Mr Abe in his Guildhall speech last month.

"Five years before John Maynard Keynes published his General Theory, Takahashi succeeded in extricating Japan from deep deflation ahead of the rest of the world. His example has emboldened me."

Takahashi's triumph was to smash expectations. "It is impossible to get rid of ingrained deflationary psychology unless you clear it out all at once. I myself have attempted to do exactly that," said Mr Abe.

There is a contradiction to the BoJ's policy. If printing money does raise inflation to a new target of 2pc, bondholders will suffer, either by a capital loss if yields jump or by slow erosion if they don't. Life insurers and pension funds might at any time refuse to buy.

But it is a question of picking the lesser poison. The Fed navigated such reefs in the late 1940s, mostly with financial repression to whittle away war-time debt. Japan can do the same. This will be horrible for pensioners.

Mr Abe has created a tailwind before he launches his blast of Thatcherite reforms, or "Third Arrow", intended to drag Japan's pre-modern service sector kicking and screaming into the 21st century, to open the rice paddies to commercial farming, to open the country to the world and, in theory, to demolish the edifice of vested interests, using the Trans Pacific Partnership as a sledgehammer.

This is the hard part. Mr Abe's Liberal Democrat Party is itself a nexus of vested interests. The party may now control parliament with its allies but can it control its own MPs?

My view is that Japan is less sclerotic and pre-Thatcherite than often claimed. The Western narrative that Japan kept zombie firms alive and put off reform after the Nikkei bubble burst in 1990 is only half true. The greater failing was monetary policy.

There are, of course, horror stories of inefficiency in Japan. Companies have "banishment rooms" where unwanted workers are shunted in the hope that they will resign, since solvent firms are not allowed to fire staff.

Yet the real crisis is demographic, and harder to solve.

Prof Masahiro Yamada, from Chuo University, says the economic depression itself has been a key reason why fertility has collapsed and why the population has been shrinking since 2005, with awful implications for ageing costs.

The reason why marriage rates among those in their 20s and 30s keeps falling is because work has become precarious. Ever fewer young men have tenure track jobs, which makes them less marriageable. They join the army of "Parasite Singles", some 3m aged 35-44 living with their parents.

The women themselves defer marriage in the hope of finding Mr Salaryman. Deflation and demography have been feeding on each other.

What seems clear is that the oldest society on earth cannot afford to waste its working women.

The gender gap between men and women in jobs is 25pc in Japan, 14pc in the US, 13pc in the UK, 12pc in Germany and 6pc in Sweden, where it is entrenched by a tax structure that penalises working couples.

Nor can Japan persist with an average retirement at 61, followed by a quarter century of taxpayer support at crippling cost.

This will be Mr Abe's real test. But without a monetary revolution, he could never even have started.

Posts: 12,025

Threads: 1,809

Joined: Apr 2008

Reputation:

227

A primer from the IMF on Abenomics

Posted on August 5, 2013 by iMFdirect

By Jerry Schiff

Discussions in Japan of the “three arrows” of Abenomics—the three major components of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s economic plan to reflate the economy—are rampant among its citizens as well as economists, journalists and policy-makers worldwide. Even J-Pop groups are recording paeans to the economic policy named after the newly-elected premier. It is clear that “Abenomics” has been a remarkable branding success. But will it equally be an economic triumph?

We think it can be, and initial signs are positive. But such success is not assured. It will require difficult decisions as the country moves into largely uncharted territory. And much will depend on changing expectations within the country.

Abenomics: Changing Minds

Following two decades of deflation, low growth and rising public debt, Japan is looking to make a clean break with its recent past. Prime Minister Abe rolled out, in late-2012 and early 2013, a comprehensive approach to reviving the Japanese economy, summarized by three policy arrows: aggressive monetary easing, flexible fiscal policy, and structural reforms to raise potential growth.

The idea is this: An escape from deflation triggered by monetary easing and fiscal stimulus would lower real interest rates and stimulate investment, consumption and—with, at least temporarily, a weaker yen—exports. Structural reforms would contribute to confidence and ensure that higher growth is sustained. Lower funding costs and higher growth would improve debt dynamics. And a credible medium-term fiscal plan would curtail risks of a government bond rate spike and allow for a measured pace of adjustment. If all goes according to plan, a more dynamic Japan would emerge, which would be an important plus for the global economy as well.

What is being attempted under Abenomics is nothing less than a leap from a low-growth deflationary equilibrium to a new equilibrium characterized by positive inflation and higher sustained growth. This will require a parallel shift toward more risk-taking, requiring changes in expectations by businesses, consumers and financial institutions, both about Japan’s growth prospects as well as the government’s ability to carry through with needed reforms. These changes will not be easy to engineer. To put it in perspective, a Japanese college student today has experienced deflation and low growth through her entire life, with nominal GDP at the same level as 1991.

An End to Incrementalism?

In early April, the first of the three arrows was fired, with the Bank of Japan announcing its new quantitative and qualitative monetary easing (QQME) framework to achieve 2 percent inflation in a stable manner within about two years. The sheer size of the planned asset purchases marks a clear departure from the incremental approach of the past, and forward guidance is aimed squarely at sending the message that QQME will continue for as long as necessary to achieve its goals. We think this new framework has a good chance of success.

But monetary policy cannot do the job alone–all three of Abe’s arrows are required. The government recently put forward a broad growth agenda, but critical details remain to be fleshed out in the coming months. With the Upper House election now complete, all eyes will be on Tokyo to see whether the structural elements of Abenomics will also represent a decisive break from the past, by directing policies at the key underlying constraints to growth. Concrete steps to raise employment, increase labor market flexibility, deregulate agriculture and the services sector, and enhance the role of the financial sector in supporting growth, would be key.

A clear and convincing plan to reverse the long-term trend of rising government debt is also needed urgently. Net public debt has increased from 13 percent in 1990 to 134 percent today, the highest among advanced economies. This rise in debt has so far been financed without problem. But the experience in the European periphery makes it clear that investors’ views can change quickly, and that reducing the debt burden will require both medium-term adjustment and higher growth. Moving forward, as planned, with the consumption tax hike next April would be a major step in the right direction.

Is it Working?

We see encouraging signs that the desired changes to the economy are beginning to take place. Growth in the first quarter rose by an impressive 4¼ percent (seasonally adjusted annual rate). Equity markets are up by some 40 percent for the year. Exports appear to be recovering. Credit growth has turned positive. Consumer and business confidence have picked up. And Inflation expectations are beginning to rise. Meanwhile, media reports abound with anecdotal evidence of recovery—it seems, for instance, that purchases of expensive tuna are now outstripping the more humble mackerel in sushi restaurants throughout Tokyo.

But the transformation is far from complete. In particular, higher investment and wages—two keys for ultimate success—are not yet observed. This should not be surprising, as businesses will need first to feel secure that the economy is moving to higher growth, while financial institutions are still sorting out the implications of recent changes for their business models. This process is also behind much of the volatility we have witnessed in Japanese financial markets in recent months.

Much can still go wrong. The global economy has been volatile and a downturn could create headwinds just as Japan’s economy is taking off. But the bigger risk is domestic, that through complacency or political obstacles we get a partial version of Abenomics, missing one or more of its key elements and failing to convince that “this time is different.”

But, for the first time in a while, there are good reasons for optimism in Japan.

Posts: 12,025

Threads: 1,809

Joined: Apr 2008

Reputation:

227

Well, inflation seems to be taken off, so far so good, one is inclined to say, but on closer inspection, there are some problems..

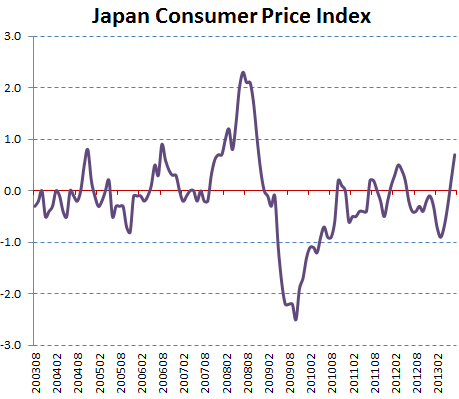

On its surface "Abenomics", which is focused on pulling Japan out of its prolonged deflationary environment, seems to be working. The CPI spiked to the highest level since 2009.

|

|

Source: Statistics Bureau |

But there are two key problems with the way this policy is progressing thus far.

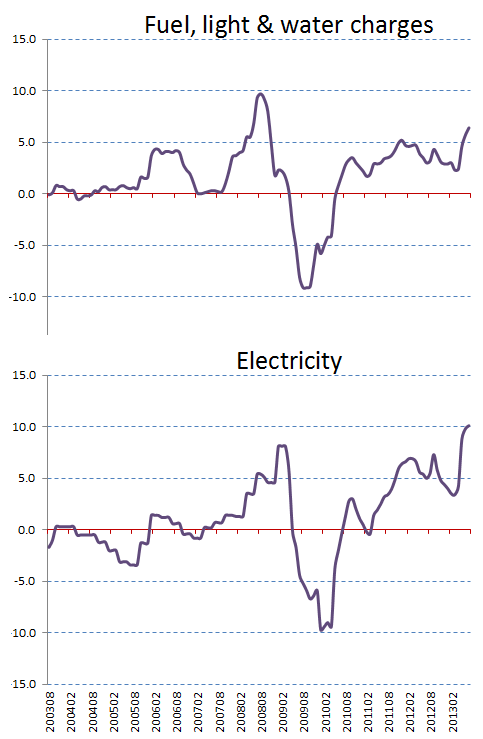

1. Price increases have been driven by weaker yen rather than pricing power improvements of domestic producers. Japan is generating the "wrong" kind of inflation - here are a couple of reasons for this recent spike in CPI.

|

|

Source: Statistics Bureau |

2. This externally driven inflation is creating negative real wage growth domestically. The concept seems to fall on deaf ears in the economics community - we've received numerous emails from seemingly educated economists who don't see anything wrong with the current trajectory of Abenomics. Japan cannot pursue this policy without some badly needed labor reforms.

Japan's corporate practice of lower (on average) wages for workers who are older than 50 (see chart) combined with rapidly aging population (increasing numbers of employees older than 50) takes wage growth in the wrong direction. The combination of declining or stagnant nominal wages and rising prices is creating serious hardships for the nation's citizens. Here is a passage from the WSJ that zeroes in on the problem with Abenomics.

WSJ: - ... for the average person in the world's third largest economy, the recent budding signs of rising prices have brought more pain than gain amid sluggish income growth.

"I pay more when I go grocery shopping. I also pay more for gasoline," said Noriko Kobayashi, who works at an advertising agency. "As my monthly salary and bonuses haven't increased, the rise in consumer prices hurts me," the 39-year-old said. "I haven't felt any benefits from Abenomics."

Ms. Kobayashi's woes are shared by millions of others across the country who have seen their purchasing power shrink, and demonstrate that in the absence of solid wage growth, inflation isn't a cure-all for the economy.

Posts: 12,025

Threads: 1,809

Joined: Apr 2008

Reputation:

227

Published: Sunday, 8 Sep 2013 | 8:50 PM ET

Kiyoshi Ota | Bloomberg |

Japan's economy expanded much faster than initially expected in the second quarter, adding to growing signs a solid recovery is taking hold and heightening the case for Prime Minister Shinzo Abe to proceed with a planned sales tax hike next year.

A marked improvement in capital expenditure led to an upward revision in April-June gross domestic product (GDP) to an annualised 3.8 percent expansion from a preliminary 2.6 percent increase, data released by the Cabinet Office showed on Monday.

The expansion, which roughly matched a median market forecast for a 3.7 percent increase, underscores the strength of Japan's recovery and boosts the chance the government will proceed with a two-staged increase in the sales tax.

(Read more: Is Japan's economic recovery gaining traction?)

It was the third straight quarter of increase following a 4.1 percent growth in January-March.

On a quarter-to-quarter basis, GDP growth was revised up to a 0.9 percent increase from a preliminary 0.6 percent.

Japan's consumer comeback

Charles Beazley, Chief Executive & President of Nikko Asset Management discusses how Abenomics has spurred a revival in Japan's economy.

Japan emerged from recession in 2012 and data for much of this year has shown the benefits of Abe's reflationary policies and the BOJ's aggressive stimulus.

Preliminary GDP data for April-June fell short of market forecasts due to weaker-than-expected capital spending, casting doubt on whether the tax hike will proceed as scheduled.

(Read more: Bank of Japan stays pat, says economy recovering)

But capital expenditure was revised up to a 1.3 percent rise from the preliminary 0.1 percent decline, suggesting that improving business sentiment is prompting companies to spend more on plant and equipment.

The data gives the government more ammunition to counter critics of the tax hike, who have called for a delay or watering down of the increase on the view Japan's economy is still too weak to weather the pain.

Abe has made ending economic stagnation among his key policy priorities, but must also be mindful of fixing Japan's tattered finances with public debt having ballooned to double the size of its $5 trillion economy due to past fiscal stimulus and the rising social welfare costs for a rapidly ageing population.

(Read more: Why the Bank of Japan is right to stay 'passive')

The government has cited revised GDP data as among key factors in deciding whether to go ahead with lifting the sales tax to 8 percent from 5 percent next April, and to 10 percent in October 2015. Abe is expected to make a decision early October.

Posts: 12,025

Threads: 1,809

Joined: Apr 2008

Reputation:

227

Bit of a mixed picture still, but there are positive signs as well

By Toru Fujioka and Chikako Mogi Dec 16, 2013 2:35 AM GMT-0300

Large Japanese businesses pared their projections for capital spending this fiscal year, signaling challenges for Abenomics as a sales-tax increase looms in April.

Big companies plan to boost spending by 4.6 percent in the year ending March 2014, a quarterly Bank of Japan report showed today. That compared with a 5.1 percent projection three months earlier. The slide contrasted with an increase in sentiment to the highest since 2007.

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is trying to convince businesses to raise wages and investment as part of efforts to catapult the nation out of a 15-year deflationary malaise. While the yen’s slide to a five year-low against the dollar last week highlighted the boost to exporters from Abenomics, companies aren’t convinced the nation’s recovery will be sustained.

“We still don’t find any evidence that corporates are really starting to get confident about the sustainability of the recovery and actually ramping up domestic investment,” Izumi Devalier, a Japan economist at HSBC Holdings Plc in Hong Kong, told Bloomberg Television. “And that remains a worry in an environment where consumption is going to weaken next year.”

The Tankan index for sentiment among large manufacturers was at 16 in December, up from from 12 in September and beating the median estimate of 15 in a Bloomberg News survey.

Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga said today the survey greatly exceeded expectations and the government will pursue economic policies with confidence.

Central Bank

The Bank of Japan’s board will not add to the unprecedented easing unleashed in April in its drive for 2 percent inflation, according to all 35 economists in a separate Bloomberg News survey.

Today’s Tankan report shows that more large companies forecast input prices rising than falling in the first three months of 2014. Output prices are seen as declining, indicating that firms lack confidence in passing on costs.

The central bank said today that it will include company price forecasts from the next Tankan survey in March.

The businesses’ inflation outlook is a source of concern, said Takeshi Minami, chief economist at Norinchukin Research Institute in Tokyo. “Input prices have to be passed on to output costs to ride out the effects of the sales-tax rise,” he said.

Pessimistic Outlook

Firms are more pessimistic in their outlooks for next quarter. The Tankan was conducted from Nov. 14 to Dec. 13 and surveyed 10,509 businesses.

The yen gained 0.4 percent to 102.85 against the dollar at 2:11 p.m. in Tokyo, after falling last week to as low as 103.92, the weakest since October 2008. The Topix stock index fell 0.9 percent as investors awaited a two-day Federal Reserve policy meeting starting tomorrow.

Large companies plan to increase investment by 8.2 percent in the six months through March from a year earlier, after capital spending was unchanged in the first half of the fiscal year.

The Tankan sentiment index for small non-manufacturers turned positive for the first time since 1992, rising to 4, with construction companies the most optimistic. The gauge for small manufacturers was 1, the first positive result since Dec. 2007.

The improvement among small firms, which also revised up their capital spending projections, suggests the recovery has broadened faster than expected, Masamichi Adachi, a senior economist at JPMorgan in Tokyo, said in a research report.

Wages Push

Abe also needs companies to raise wages if Abenomics is to succeed, and has called four meetings since September with union and business leaders to try to persuade them to do so.

“We respect his request,” Honda Motor Co. Executive Vice President Tetsuo Iwamura said in an interview on Dec. 12. “Our first priority is to improve profitability. Then we will consider the reward for our stakeholders and our associates.”

Salaries excluding overtime and bonuses fell for a 17th straight month in October after a 1.5 percent decline in the decade through 2012.

|